Not without hope

Somewhere along the bends of the lower Santee River, Bartholomew Gaillard set his feet and decided he would stay. Like many Huguenots, his flight from France landed him in the warm, lush, and mosquito-ridden Carolinas. Little could he have known gazing out across those Santee waters that he would father a line of politically active, wealthy, and prominent South Carolinian men.

Bartholomew’s son, Theodore Gaillard Sr., received grants for at least 7,975 acres in Craven County. He ultimately owned three plantations with 136 enslaved persons and an additional home outside Charleston, establishing a wealth that would greatly serve his children and descendants. Theodore Sr. was active in his community and held a variety of positions from chapel building commissioner to tax collector. Theodore’s own son, John Gaillard Sr., amassed significant property (to be exact: two plantations—named Perdrieau and Lewisville— and 84 enslaved persons) and participated greatly in public service. Also similar to each other, both Theodore Sr. and John Sr. both initially supported the colonies during the American Revolution, but switched sides mid-way through when Britain invaded South Carolina. Because of their support of the loyalist militia, the General Assembly confiscated their estates and banished them to England. Fortunately for the Gaillard family, however, they were able to regain the majority of their properties and return to the Carolinas.

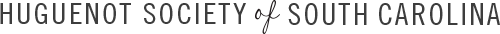

With the tumultuous waves of the Revolution—and the Atlantic—behind them, the next generation of Gaillards grew up on established plantations in a barely-established new country. Notably among them was Senator John Gaillard Jr. (figure 1) who, to the same tune of interest as his father and grandfather before him, had his eye on politics. He served for 21 years and was elected as President Pro Tempore of the Senate nine times and it was said that “he seemed born for that station”[1]. Senator Gaillard was so committed to the role that upon his death in 1828, he was still in office. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

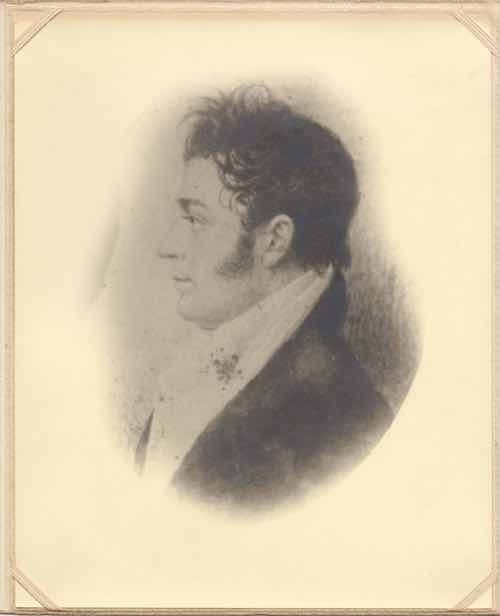

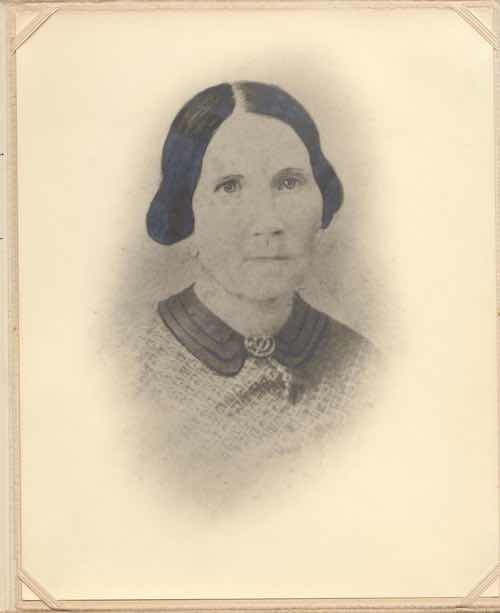

His son, Dr. Theodore Samuel Gaillard (figure 2), born in 1796, graduated from Yale University by 18 years old. He married Francis West (figure 3), who travelled from Maine to Charleston so that the warm coastal air might ease her “frail condition” (as stated in the inscription beside her portrait). The two had sixteen children and are buried together at St. Stephen’s Cemetery in South Carolina. On Theodore Samuel’s grave are words that might have resonated with his Huguenot great-great-grandfather as he set foot upon the banks of the Santee River: “Our sorrow is not without hope.”

Huguenot Society of South Carolina. Transactions of the Huguenot Society of South Carolina. Vol. 5, Charleston, S.C., Press of Walker, Evans & Cogswell Co., 1897, pp. 91-95.References"Dr Theodore Samuel Gaillard." Find a Grave, 24 May 2007, www.findagrave.com/memorial/19508164/theodore-samuel-gaillard.Edgar, Walter B., and N L. Bailey. The Commons House of Assembly 1692-1775. 1 ed., vol. 2, Columbia, S.C., University of South Carolina Press, 1977, pp. 264-67. Biographical Directory of the South Carolina House of Representatives.Huguenot Society of South Carolina. Transactions of the Huguenot Society of South Carolina. Vol. 5, Charleston, S.C., Press of Walker, Evans & Cogswell Co., 1897, pp. 91-95.Huguenot Society of South Carolina. Transactions of the Huguenot Society of South Carolina. Vol. 80, Columbia, S.C., The R.L. Bryan Company, 1975, pp. 140-143.Morgan, Mary L., et al. Biographical Directory of the South Carolina Senate 1776-1985. 1 ed., vol. 1, Columbia, S.C., University of South Carolina Press, 1986, pp. 539-40.